Across 110th St. - A Harlem Photo Essay

I was the third brother of five,

Doing whatever I had to do to survive.

I'm not saying what I did was alright,

Trying to break out of the ghetto was a day to day fight.

Been down so long, getting up didn't cross my mind,

I knew there was a better way of life that I was just trying to find.

You don't know what you'll do until you're put under pressure,

Across 110th Street is a hell of a tester.

Doing whatever I had to do to survive.

I'm not saying what I did was alright,

Trying to break out of the ghetto was a day to day fight.

Been down so long, getting up didn't cross my mind,

I knew there was a better way of life that I was just trying to find.

You don't know what you'll do until you're put under pressure,

Across 110th Street is a hell of a tester.

Bobby Womack "Across 110th St."

In large measure, the aggressive policing policies - including the recently challenged "Stop and Frisk" - that have made NYC one of the safest cities in America, have also enabled a largely white and affluent return to Manhattan and Harlem specifically. Nowhere is it more clear that the mission of the police is to protect and serve the interests of property and wealth. NYPD is present in Harlem in a way that it never was in previous eras, strategically positioned at the outposts of corporate development, stationed outside of the Chase Bank, Staples, Starbucks, GAP, and American Apparel, to name just a few.

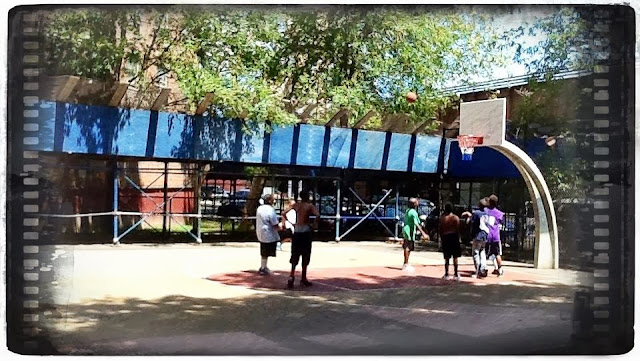

The following Harlem Photo Essay is my attempt to chronicle a little moment of this process of gentrification. My photos emphasize areas of transition, the vestiges of a decaying African American past, and the movement of Harlem's remaining African American citizens through this landscape of change. I've grouped my photographs in 8 different sub-headings:

I. The Evidence of Gentrification and Corporatism

II. The Last Vestiges of a Black Community History

III. Black Harlemites Just Making a Way Out of No Way

IV. The Changing Ethnic Makeup of Harlem and Tourism

V. The Enduring Black Church

VI. The Projects on the Margins

VII. Black Entrepreneurship

VIII. The Changing Physical Landscape of Harlem

I took these pictures August 3 through 10 between 110th and 145th Sts. (south to north) and St. Nicholas Ave. and Park Ave. by the trains and the Harlem river (east to west). Malcolm X / Lenox Blvd, Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. Blvd., and 125th/Martin Luther King, Jr. Blvd. were

emphasized.

Part I. The Evidence of Urban Gentrification and Corporatism

If you remember Harlem in the 1990s or earlier, many of these photos will be quite striking. Look, I am not lamenting the loss of a ghetto. I have no sentimentality for poverty. I am critiquing racist political and economic processes that intentionally prevent African American citizens of Harlem, who have suffered so long amidst the hopelessness and despair of Harlem -the quintessential American ghetto- from enjoying any of the benefits of contemporary redevelopment and urban uplift. I am critiquing generations of predatory slumlords and neglected properties and predatory policing. I am critiquing all those who would claim that the unfettered free market provides the ultimate answer to poverty. Although it is clear that the influx of large corporate firms provides some employment to the African American residents of Harlem, there is no real indication that this employment provides wages that enable Black Harlemites to markedly improve their social class.

*

Part II. The Last Vestiges of a Black Community History

Everywhere you see the last vestiges of great Black institutions that Harlemites relied on through the many eras of racial segregation. The Amsterdam News, a venerable Harlem newspaper, is a classic example of such segregated institutions. When the NY Times refuses to print stories relevant to your daily life, and, in effect pretends that you don't even exist, you have to turn the pages of the Amsterdam News in order to know what's really going on. But the Black United Fund and the Harlem YMCA and street names and murals of Malcolm X and statues of Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. all speak to what Harlem has been as a Black cultural force. This is Black capital of the urban north. This was home to Garvey and Malcolm and Duke and Bird.

Part III. Black Harlemites Just Making a Way Out of No Way

There are real lives being lived in the midst of the larger historical forces of gentrification and ethnic out-migration. I remain moved by the on-going resolve of Black Harlemites. For so long Black Harlemites lived within the specter of the ghetto in a perpetual state of hopelessness and despair, and now that they have come to see their neighborhoods finally improved, they must surely be cognizant that with each passing day, they are no longer welcome, and that an unwelcome change is well underway.

Part IV. The Changing Ethnic Makeup of Harlem and Tourism

There's little doubt that redevelopment, gentrification, and corporate reinvestment have produced a changing ethnic makeup in Harlem. But this is about more than race, it's about race and class and the way that developers and real estate moguls and the city are conspiring to enforce the out-migration of Harlem Black poor and lower middle class.

Tourist buses are a common site, enhancing that "living museum" feel of Black Harlem, but in context, loads of tourists in double-decker buses look suspiciously more like convoys of prospective future tenants and apartment owners. Where once it was the forbidden zone where all but a few brave souls dared to journey in seek of brown sugar fantasies, Harlem is now open territory, ripe for affluent whites who fled the confines of Manhattan generations ago.

It's also clear that the very last remnants of Black property ownership in Harlem, as in every gentrified formerly Black urban enclave, will be the Black churches, if for no other reason than the very smart and progressive efforts of so many Black churches to pay off their mortgages. The continued existence of these churches, many of which have congregations that commute from outside of Harlem, is a testament to the power of collectivism as a strategy for beating the capitalist game. By pooling money and resources, Black congregants have managed to hold on to their properties and are now certainly watching their property values rise in the midst of gentrification. Hold on brothers and sisters! You may well be the last living Black Harlemites!

Part VI. The Projects on the Margins

*

There remains limited Black ownership of property and entrepreneurship in Harlem. The occasional new cafe, chicken shack, barbershop, hat shop, salon, and restaurant are very encouraging. This is, in my opinion, what a New Harlem should look like, with a thriving economy based on Black-owned small businesses. However, struggling watermelon street sellers and hustling street vendors peddling used Black books, blaxploitation dvd's, hair care products and caps, are also an ever-present reality in the shadow of corporate retailers like H&M and Verizon, where the real money is being made. They demonstrate the enduring and intentional racialized failures of capitalism. How difficult must it be for a Black small businessman to get a loan and profit from Harlem's urban gentrification?

Harlem is now one massive construction site, and has a physical landscape dominated by scaffolding and busy construction crews. Gentrification has brought an entirely new look to parts of the neighborhood. People tell me that before gentrification, there were no driveways in Harlem. You are starting to see them because a lot of the new construction includes garages where upscale professionals can park their expensive cars. But this is not all. Many of Harlem's refurbished apartment buildings simply look different, as though transplanted from Chelsea or Park Avenue. Maybe Harlem's re-development isn't simply geared toward white hipsters working internet start-ups but also corporate middle and upper management and bigger money on Wall Street, banking, international commerce, law and real estate.

In the immortal lyrics of the great Bobby Womack, "Across 110th St. is a hell of a tester."

l shot these photographs using a Panasonic Lumix DMC-ZS19 HD pocket camera (although two of the photographs indicated by an asterisk * were shot using an iPad2 camera). Photo effects and enhancements including clarity, textures, and frames were added using Photo Toaster and Camera Awesome apps for the Apple iPad. I used Picassa Web Albums to organize the photos and coordinate between my camera, the iPad, Macbook Pro and my Google+ blog.

Opening of "Across 110th St." with Yaphet Kotto featuring the music of Bobby Womack